CMON: Rise of the Kickstarter Zombie giant

How the company went from a website to a boardgame giant, and then failed to make money out of it

CMON stands for CoolMiniOrNot. That was the name of the website David Doust and Chern Ann Ng (mostly the latter) created in 2001. Inspired by Hot or Not, it was a website that allowed users to rate how well a miniature was painted. It was 2001 and one, and the wargaming community didn’t have that many places to get together, so it was fairly successful. After a few years of operating the site, Doust and Ng realized they had a good audience to start distributing games from the site, and later started publishing their own games.

The way they decided to go at it was pretty innovative at the time. They didn’t have a huge amount of capital, so they did two things to make their start smoother:

Outsource all their production to factories in China in made-to-order batches

To know in advance the size of the batches and get financing for the orders, do the sales through Kickstarter.

Now, those things are pretty run-of-the-mill today, and many other companies use them, but Zombicide was pretty much pioneering the approach. Thanks to good marketing and a timely (and serendipitous) collaboration with Penny Arcade1, that first Kickstarter went on to sell almost 800,000 $, and Zombicide went on to become one of the biggest-selling franchises in board games, racking up more than 30 USD M in sales only through Kickstarter (more if you add Marvel Zombies). CMON went on to get VC financing, and IPO in Hong Kong in 2016 and has kept making games ever since, both creating their own and publishing others’ games.

In the time since their IPO, they have gone from 20 USD M in revenue in 2016 to 45 in the last year. Maybe not a huge home run, but quite a decent result. And the business model is supposed to be very asset-light. CMON is in charge of the development of the games and their promotion for Kickstarter, but the manufacturing is outsourced, as are the logistics and more traditional distribution channels too (through agreements with companies like Asmodee or Edge - now part of Asmodee, whose company gobbling rampage is an interesting theme for another time). What that leaves you with is a relatively small corporate overhead (78 employees as of 2022, at almost 600,000 $ per employee) and less sensitivity to volumes than other companies. Not only that, but they have access to very relevant 0-cost financing for a big part of their inventory through Kickstarter. When you are selling a high-margin product (and their gross margins used to hover around 50% until 2020, and even now are at around 40%), that should be a recipe for boatloads of cash if you have decent volume.

So the question I am trying to answer today is why the stock price has collapsed by 85% since 2017, and why rather than being a cash printer CMON has been unable to pay any dividend at all so far, and has ended up in significant debt.

A story of costs and efficiency

CMONs gross margins have been eroding over time. From 51% at IPO to its current 40% there is quite some difference. A big reason for the erosion has been the cost of inventories, which has jumped from 32% of revenues in 2015 and 34% in 2016 to more than 38% in 2022. The cost of shipping & handling merchandise has also gone up slightly (12% in 2015-2016 to 14% last year), but there the picture is a bit muddier. Up until 2018, the expenses in shipping were more or less offset by the charges they made on shipping to the clients. But from then onwards, CMON is expending more than 2 USD M a year net, excepting 2019 (no data) and 2020 (where they made a profit, oddly enough).

But the rest of the expenses included in the cost of sales have jumped from 2% in 2016 (3.8% in 2015) to consistently getting close to 7% of revenues or above that. Those expenses are amortization related to capitalized game development costs and tooling, inventory depreciation… there is a lot in there but in general points to a loss of efficiency in the company, or a loss of margin due to the sales mix. But since Kickstarter still dominates in the mix, let's focus on the efficiency angle.

That is further supported by their fixed costs. See… 40% is still a healthy gross margin for most businesses. But the problem with CMON is that their SDGA (Selling, distribution, general and administrative) costs have gone from 22% of revenues to 38% of revenues since 2015. And to make it worse, once you exclude the money they spent on getting listed and the merchant account fees (that are variable and depend on Kickstarter revenue), in 2015 and 2016 it was below 10%, while in 2017 it jumps to 29% and now it sits at 34%.

So… what happened in 2017?

The problems of having money

Some companies seem to be better off without having easy access to money. Before the IPO and VC financing, CMON was doing quite alright. in 2015, even after paying 2 USD M in costs related to preparation for listing, CMON was making a healthy profit (almost 2 USD M). It had 29 employees, and very little fixed costs (that I estimate at around 3 USD M).

In 2017, after IPO and an infusion of capital, there were 66 employees, their lease expenses and traveling expenses had multiplied by 4, and their non-capitalized games development expenses by 3... Their fixed costs, by my estimation, were at this point around 8 or 9 USD M. Sales did well and increased by 70% in the same period, but then stagnated. And CMON found itself with a structure prepared for massive growth, and the massive growth not showing up. And that, in turn, made the company’s economic model (with a lot of operational leverage built into it) change. Now we have a high fixed cost (for their revenue) company that needs to chase revenue to keep surviving instead of a scrappy company that generates quite a bit of money.

This is also apparent when you look at the investment side. In 2017 CMON also purchased a new office for more than 4 USD M (part of which they announced recently they are selling, probably to pay down part of their debt and reduce their financing costs). Investments also ramped up in art and sculptures (which, in my view, should be in the expenses and not capitalized, since this is mostly useful to promote games). Investment in intangible assets (capitalized development costs and purchases of IP) has been more moderate, and the spike in 2017 was caused by the purchase of valuable IPs (Rising Sun, World of SMOG).

But overall, the result is that CMON now seems relatively capital intensive, with 19.5 USD M in fixed assets versus 2.7 in 2015. And of those, 13.4 USD M are classified as “art, paintings and sculpts”. Unless CMON is investing in paintings on the side, those are most likely promotional materials for their games to display at cons and similar events. I don’t think they can sell them for anything close to that amount, and we should think of them as expenses, regardless of their actuarial classification.

Once you subtract the carrying value of the offices (3.8 USD M, it is real state after all, and can be sold as proven above) and the art, you are left with a much more reasonable 2.3 USD M. The good news is CMON is still capital-light. The bad news is that if those 13.4 USD M had been classified as expenses, 70% of the book value would be wiped out and tangible equity would be negative. Oooops.

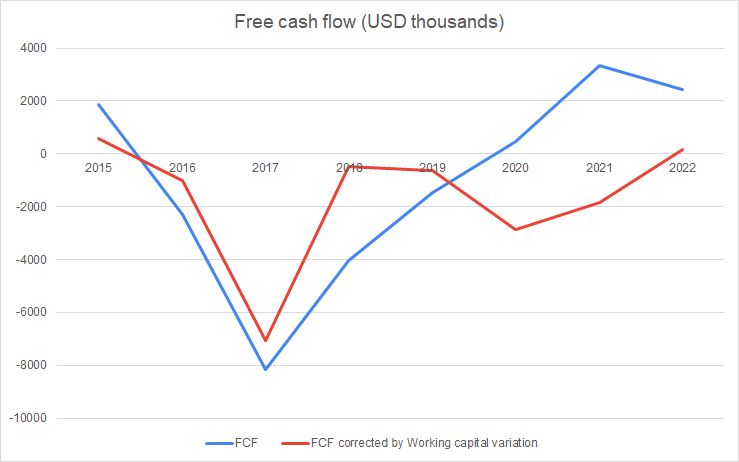

The company also has had trouble generating cash, of course. Even the cash generated in the last couple of years is suspect, as it comes in good measure from the increase in Kickstarter sales. Since in that case the cash is paid upfront, an increase in YoY sales translates into cash generation, but a decrease would have the opposite effect. Another part, in 2021, comes as a result of the delays in manufacturing in 2020 (they had prepaid for a lot of inventory).

To make it worse, they had hit their Kickstarter sales ceiling, and their sales through other channels did not pick up. Instead of scaling down, the company went on to focus on trying to improve sales through several attempts, and we will analyze them now. But I think this is the first pitfall and a very relevant one: getting money you don’t need to grow before actually growing in sales. It is a phenomenon we see relatively often in the tech sector, but maybe not so common in others. This has left a company that is now extremely sensitive to hiccups, and with enough leverage that a reduction in sales (especially Kickstarter ones) could cause serious trouble.

What happened with CMONs revenue?

While we have seen what happened with the costs, the other side is that the revenues did not grow as much as the company seemed to expect. In my view, there are two sides to this. One is the relative failure to expand its product line-up, and the subsequent strategies it followed to increase sales, and another is the failure of building a sustainable distribution strategy for its size.

CMON’s one-time payment model

The idea at the heart of early CMON products is fairly simple, and a good one too. Miniatures are cool, but very few people have both the time and the money to build armies that cost a mint and invest tons of time in learning a game that takes 5 or 6 hours to play. So let’s build simpler self-contained games, closer to specialist board games than to, say Warhammer. That simple approach is what made Zombicide and others (like Bloodborne, Massive Darkness, Rising Sun, or Ankh) very successful games. There is a difficult problem to solve in this market, and that is generating repeat sales. Games can do very well on launch, but then, unless they become staples, sell pretty much nothing afterward. And CMON’s model accentuates that.

CMON mostly relies on games published on Kickstarter, and that means all the buzz is around the initial launch there. Not only that, but that buzz is far apart from its availability on other channels (because it is made after the Kickstarter closes and with that financing). And then there are the Kickstarter exclusives. To capitalize on FOMO and increase sales on Kickstarter several companies have started to offer several packs while the Kickstarter is taking place, many of them labeled as exclusives and that won’t be available through other channels after, along with rewards exclusive to Kickstarter at several levels of funding. This makes the versions available through other channels even less desirable. Not only there is little promo or buzz when they are available, they are worse than the versions players are getting to know by word of mouth. As an example, Zombicide White Death had 11 expansions not included in the basic pledge, which you could get in one bundle (paying 380$) or piecemeal in the pledge manager (base pledge being 110$). Both included all the stretch goals (around 60 miniatures that will not be in the retail version).

That last case also brings to the fore another problem CMON has: they have peaked in Kickstarter. It is a relatively small channel, and it is tough to break 20,000 backers, and almost impossible to break 30,000 (CMON managed it once, with Rising Sun). A few games have managed to go far beyond that, but most of them had much lower price points (Frosthaven being the most obvious exception and record-breaking game, 40% ahead of CMON’s record, 4th in the classification)

This can be a great model for a small studio or publisher, and overall if you don’t have great fixed costs. But as we saw above, CMON is no longer that, so it needs also some recurring revenue.

There are ways to do that. One is something that you can see in other games, like Ticket to Ride, Dominion, or Catan: expansions and slightly different versions from time to time that expand consolidated games and keep them alive, even selling copies of the base game. But that is difficult for a company that has no real distribution network, and that relies on Kickstarter numbers to order a limited run from their suppliers.

The distribution part could have been circumvented with a strong DTC activity, and CMON tried with an online store. However, they never managed to sell much (4% in their best year, or 1.2 USD M) and decided to discontinue it. To be fair, they never managed to do much in terms of having an online community that they could leverage for that, and their social network presence is vestigial at best nowadays. I don’t know why they didn’t try setting it up through Amazon or similar partnerships, but I guess that it interfered with the distribution agreements they have with Asmodee in some regions.

CMON also tried to improve on distribution, to try to sell their own games and those they published. First by attempting distribution to wholesalers on its own in North America and Asia and partnering in others, and then partnering with Asmodee in North America as well. This has been somewhat successful. Wholesaler sales rest at around 20 USD M in both 2021 and 2022, a long way from the 7 USD M in 2015, and the trajectory has been good (2020 excepted). But that has been against very strong growth in the hobby area in general. According to ICv2 estimations, the hobby games market in North America was around 1 billion in 2015 versus almost 3 in 2022. That is, CMON’s wholesaler growth has been just in line with the category growth.

Looking at their current Kickstarter projects, even if recognized revenue goes up because of the timing, it seems like cash will go down unless some gigantic success happens in the second part of the year, so let’s see what effect it has on their results.

CMON’s attempts to expand the catalog

CMON’s people know they have a problem with the model mismatch between the company and the structure, and they have been trying hard to expand the company’s model so it works well.

One of the first things they tried is to become not only a company that creates games, but a publisher. Just like it happens in the videogame industry, in board games we have game studios and publishers. Publishers usually own studios or have their own and then use their existing relationships and capacity to also publish games from other actors (usually independent designers that receive an advance and a cut, much like in book publishing, and in other cases the designer is hired as a consultant to develop the game). And CMON tried to become one since they already had some distribution capacity. Some of the games they have published include a new edition of Classic Art and Sheriff of Nottingham (along with other publishers), Monolyth, Bug Hunt, Fairy Tale Inn…

Sadly, none of those CMON published as the main publisher made it. It is not entirely surprising. CMON’s strength was always promoting very well. their games on Kickstarter, not the overall distribution business, which went up only after associating with Asmodee. They are only running a few (4-5) of those a year to avoid fatigue, so they reserve it for their own miniature games. So if you are going to depend on Asmodee’s distribution anyway, why would you go with CMON, if you have the choice? Chances are that either your deal is worse (because Asmodee gets a cut) or your sales are worse (because they won’t push it as hard). Or worse, both. That means it is unlikely for CMON to get anything other than leftovers.

But that is not the only thing they have tried! When talking about hobby channel games, there are two truly big names. Asmodee, with a tremendous range of games, products, and brands, and Games Workshop, that only sells miniatures for Warhammer 40k and Warhammer: Age Of Sigmar. Since part of the good fortune of Asmodee is based on Atomic Mass Games and their Star Wars wargames sales, the conclusion is obviously that having a healthy wargame in your range can be pretty profitable.

And it is! You can extend the life of a wargame almost indefinitely, with re-editions, new units, new rules… you do it in small increments, and if they hit it off it will revitalize the games of existing inventory as well. But it also thrives on network effects and it is really hard to break into. This is a category Games Workshop simply dominates at will, inventory issues aside. X-wing managed to give them a run for their money in 2016 and 2017, but that was a combination of Games Workshop in crisis, the Star Wars license, and the backing of a giant like Asmodee. All that combined got them to second place for a few quarters, and back on top by 2018.

It is also a heavily concentrated industry. Games Workshop sold more than 500 USD M in the last reported year. According to ICv2, CMON had the 9th best-selling miniatures game in North America, vs. Games Workshop’s 1st and 2nd. CMON sold 2.5 USD M globally.

But let’s go step by step… what is this wargame and how did CMON end up in this situation?

Wargaming was in CMON’s DNA from the start. Most of the miniatures in CoolMiniOrNot.com were from wargames! Mostly Warhammer 40k, but Confrontation and other smaller games were also around. Aside from their boxed sets, they started publishing wargames from the beginning. Dark Age, Wrath of Kings… I think there was a third one, but I have forgotten, and I had to check the other two. All combined, they were selling 189,000 USD in 2016. CMON continued some development of those games until 2017, but only half-heartedly, they knew it had failed.

But in 2017 they did something much bigger. They acquired the license for A Song of Ice and Fire (books, not the tv show) and created a wargame out of it, Kickstarter included. While the Kickstarter itself only reached 1.7 USD M, they sold more than 4 million in war games in 2018. Sadly, sales deflated to half of that quickly, and while there has been some recovery, I don’t think CMON can win here.

The game has potential and has good reviews, but making a wargame grow is more similar to growing a delivery company than other types of board games. It is extremely local because wargames are an all-consuming hobby. Painting and playing take up a lot of your free time, so you need all your miniature-buying friends (and there are not that many) to be playing the same thing. There are some exceptions (again, X-wing), but overall you need to have a strong base in an area, and then you can expand to others. It is actually what Games Workshop did (reinvest the UK profits in the European and US expansion).

That requires time, connection with the community, and investment. Sadly, I don’t think CMON has any of those.

Are licenses CMON’s salvation?

There is one last thing that, if you are following the company, you might have noticed in the last few years. Almost all their Kickstarter projects are either Zombicide or some licensed property. The most relevant one has been Marvel United (along with Spin Master Games, another interesting company), but we have seen Dune, Warner Bros Animation, Masters of the Universe, and Cyberpunk around too, with upcoming games for Assasins Creed, and a game based on Stranger Things published outside Kickstarter.

Overall, I think it has been a nice move, especially the Marvel United license, which covers the 3 most successful Kickstarter projects the company has made in the last 3 years. It comes at a cost (in terms of royalties paid to the holder of the license, Spin Master in this case) but guarantees seem to be quite low, and the percentage is not too high. They paid 2.5 M USD in royalties in 2022. We don’t know how much Marvel United games sold that year, but it was way more than the 9 M USD in the Marvel Zombies Kickstarter, that was recognized as revenue that year. The amount from Kickstarter projects of CMON is always bigger than the headline number because of changes in the pledge manager and retail pledges, sometimes as much as 30% bigger (comparing revenue recognition with Kickstarter numbers, even after taking into account shipping). And there are also all the prior Marvel United products. I think we can conservatively estimate 14 M USD of revenue from all the series. And those are the total royalties, and I think they might be paying around 800,000 in other royalties (based on what they paid pre-marvel and launches after). 12% is a lot (if this is in the ballpark), but it could be a lot worse.

The problem is that their most successful line is no longer theirs. They still have Zombicide, of course, but since Eric Lang left in 2020 they don’t seem to have been doing that great developing games aside from licenses even if non-capitalized game development costs have multiplied by 3 from 2019, reaching 3.7 USD M. The licenses are helping keep the revenue up but… CMON doesn’t feel like a reliable IP developer anymore. And in this industry that kills your margins, as the owners of the IP squeeze you for more money.

Lack of focus can be expensive

After all of this, that simple phrase above is my conclusion. CMON was a profitable small-ish company doing Kickstarter-focused games. Then they took funding and got ahead of themselves, trying to do too many things at once. Publishing, distribution, Kickstarters, wargames at scale… and that backfired, consuming the money they raised and quite a bit more.

My impression is that they are in a tough spot now right now. I hope I can come back at some point with better news. Let me know what you think about the company and if there is something else you would like to know about it.

Thanks for reading, and let’s keep looking for loot!